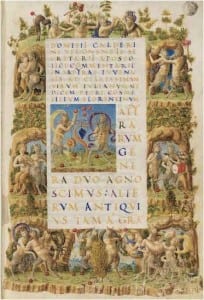

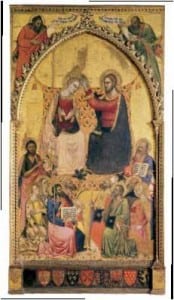

Come limitare la «indomitam feminarum bestialitatem», l’indomita bestialità delle donne? chiese un membro del Comune di Firenze discutendo delle leggi suntuarie. La donna raggiungeva il culmine della purezza nella Vergine, e un abisso di depravazione nella moglie che sperperava un patrimonio in sete e gioielli. Ma nell’arte gli opposti si conciliano: qui la pura Madonna porta tutti gli abiti sfarzosi vietati dalla legge.

How to curb the “indomitam feminarum bestialitatem”—the indomitable bestiality of our women? asked one member of the Florence commune in a discussion of the sumptuary laws. Woman was the height of purity in the Madonna and the depth of depravity in the wife who frittered away a family fortune on silks and jewels. But in art the two could be reconciled: here the pure Madonna wears all the rich clothes forbidden by law. Mother and child are good as gold.